"What, to the slave, is your 4th of July?"

And other urgent questions for this week of "freedom" celebrations

“What, to the slave, is your Fourth of July?”

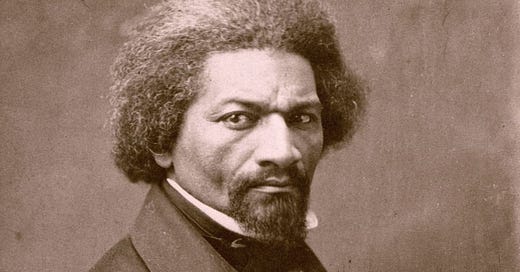

This now-famous question was posed by Frederick Douglass to a crowd of white abolitionists in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852, at a commemoration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Douglass’s hosts surely expected a barnburner of a speech from the esteemed orator and formerly enslaved abolitionist. What they got was arguably one of the most incisive, critical speeches in American history.

Hearing young descendants of Frederick Douglass recite the famous "Fourth of July" speech has inadvertently (thanks be to the algorithm) become an annual ritual of mine over the last few years. You can also read the potent speech in its entirety here.

Douglass’s words are weighing heavy on me this week, rattling around in my spirit, provoking me to ask:

What, to…

…the immigrant or refugee…

…the person seeking reproductive justice…

…the Palestinian…

…the parent of a trans child whose gender affirming care has been stripped away…

…Black people in Trump’s America…

is the Fourth of July?

Douglass calls those of us who claim to care about justice to dig deeper, risk more, and refuse the comfort our privileges may afford us, for the sake of the freedom and flourishing of those who are oppressed.

Today, I want to uplift a few points from the speech as catalysts for reflection. I hope Douglass’s words challenge and empower us as Soulful Revolutionaries — people who would take hold of the present moment with all the passion we can muster, as we courageously contend together for a world where all people are free.

The dissonance of this day

This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn…. Fellow-citizens, above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.

Douglass’s speech is predicated on the irony that a group of white abolitionists would commemorate the Fourth of July as a day of freedom, while those for whom they advocate remain enslaved.

This irony would not have been news to this audience. This was a group of people engaged in the major justice issue of their day, with most likely giving regular thought to the blatant hypocrisy of a nation claiming “liberty and justice for all” as its distinctive, while enslaving more than 10% of its population. Nevertheless, they chose to organize a July Fourth commemoration, apparently taking some pride in the Founding Fathers — of whom 41 of 56 were enslavers.

Douglass wields this irony incisively, refusing to allow his audience a moment of comfort in the celebration. Unwilling to let them rest on the laurels of knowing better, he compels them to really sit with the dissonance of this day, in order that they might do better. He demands his listeners keep their ears attuned to the oppressed, and their voices amplifying the stories of the enslaved, especially when the volume of the dominant narrative threatens to drown those voices out.

There is no pride to be taken in simply being aware. Awaking to injustice must be followed by action. And this action must be applied consistently. The work of justice is not a fad. It’s not work to be taken up when it is socially expedient to do so. On the contrary, it is all the more important to stay the course when supremacist fervor crescendos and nuance falls away in favor of unadulterated nationalism — as is especially true on July 4.

Interestingly, Douglass agreed to give this speech, which seems to indicate that the abolitionist had faith in his audience to withstand a hefty dose of dissonance. There is something incredibly empowering about a speech that doesn’t hold its punches, but treats the listener as strong enough to handle the truth. Along with his original listeners, we have much to gain by sticking with him through the end.

Doing so is a small way to practice a crucial skill for any Soulful Revolutionary: remaining attuned to dissonance while not going numb.

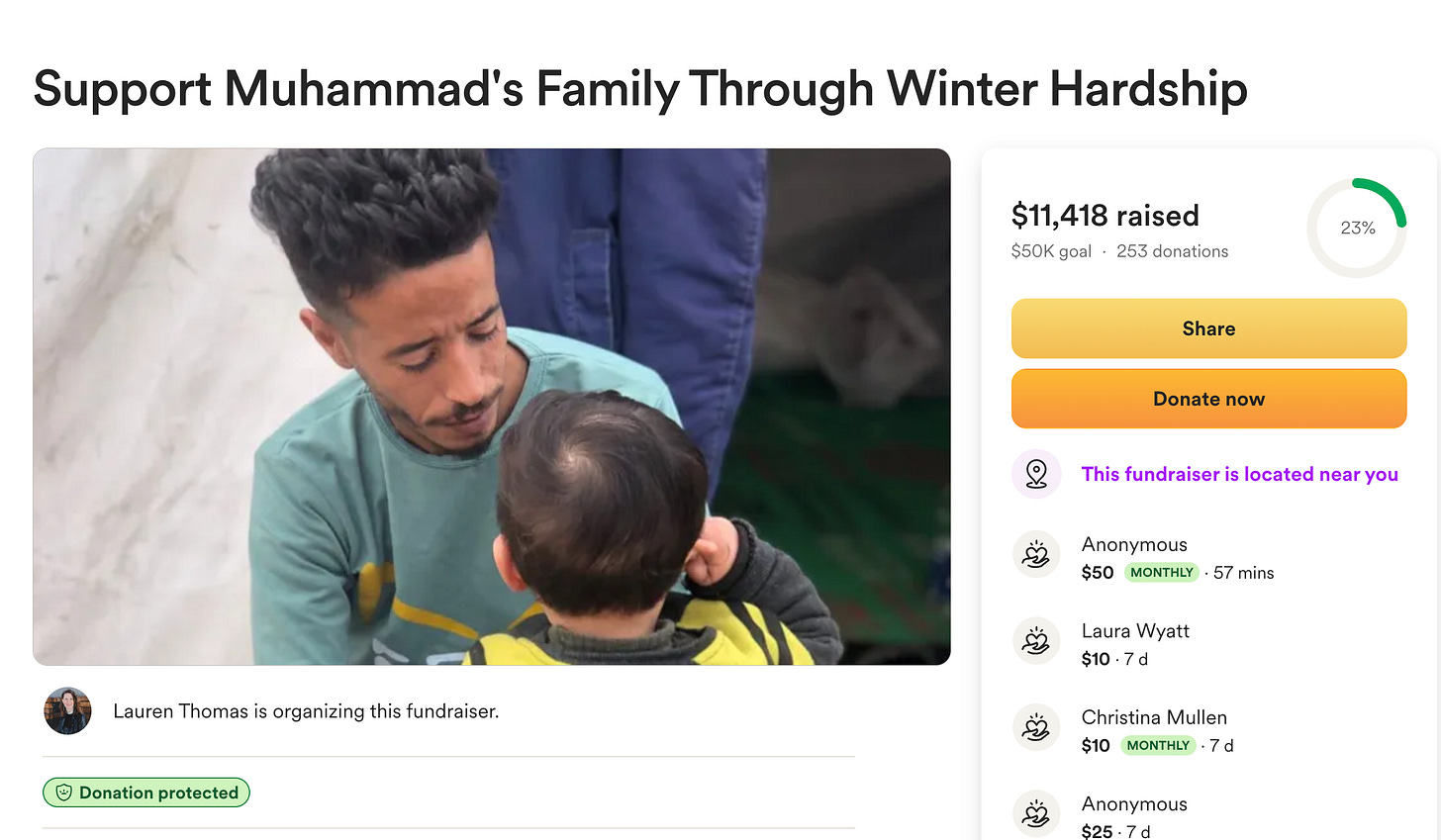

The other day, I took my children to the park. As I watched them play, I thought of my friend Muhammad in Gaza, who is not free to enjoy his two beautiful children in peace. I held joy and grief in my heart, together, at the same time.

This is the immense irony of my life — that I am experiencing the most profound joy I have known, as the mother of beautiful, healthy twin toddlers, while grieving for my friend who is terrified of being killed by bombs, snipers, or starvation, and therefore not being able to care for his wife and children.

From Wednesday of last week through Monday of this week, I didn’t hear from Muhammad, with whom I typically message a couple days a week. Whenever this happens, there are two thoughts that run through my head: 1) He is dead, and 2) Israel has shut off the internet in Gaza again.

Every time so far, it has been the latter.

This is the backdrop of my life now.

As I parent. As I write. As I pastor. As I go to the grocery store and clean my house and drive my car to get the oil changed… I desperately hope for Muhammad’s survival.

I laugh with my children and yearn for my friend to have the same opportunity with his own dear ones. I weep for the world in which these realities unfold concurrently.

And life in this dissonance demands love-fueled action from me (including my ongoing efforts to help Muhammad feed his family, which you can support here).

I wonder what the dissonance demands of you.

“I shall see this day…from the slave's point of view.”

Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery – the great sin and shame of America!

What is the lens we will consistently apply to the world? Douglass may have been a free man, but he refused to take off the lens of the enslaved. Indeed, he did not see himself, or any of his fellow citizens, as free, while his people remained in bondage. This was the perspective from which he insisted on speaking. He would not — could not — take that lens off for a day in order to join in celebrating the Fourth of July.

There have been many ways to speak of such preferential perspective-taking.

Jesus’ ministry lifted up the “least of these,” while the Bible consistently highlights the stranger (aka immigrants), the widow, and the orphan as those who ought to be prioritized for the sake of the whole society’s well-being.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor and theologian who resisted the Christofascism of the Third Reich, himself deeply influenced by Black liberation theology, operated from the “view from below.”

The mystic and theologian Dr. Howard Thurman, whose book Jesus and the Disinherited was carried by Dr. King wherever he went, emphasized those with their “backs against the wall.”

There’s no question that for Douglass, God dwells with the oppressed. Anyone who seeks to know God will be found here too.

To be in solidarity with the oppressed is to hear the drone of grief perpetually in the background, to have the constant hum in our heads of the hurts carried by our siblings.

Violence tries to drown out this sound, but it is irrepressible. It only grows in us, springing forth from the divine love in our souls, the solidarity we know as true when we allow our hearts to break open. It flows from the inner wisdom that there is no being from whom we are separate. That we are interconnected, interdependent, “tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,” as Dr. King put it.

I told a good friend the other day that my theology has imploded under the weight of Palestine’s suffering, and I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to put it together again.

Nor am I confident that I should.

As Palestinian pastor, the Rev. Dr. Munther Isaac puts it, “Christ is under the rubble.” If I am to consider myself a Christian, than this is precisely where I must seek to be:

My heart has been shattered. My soul is heavy with grief for all the crushed and bleeding beloveds of God.

I carry Palestine with me every day, and this point of view has altered the relationships I prioritize, the way I consume, what I create, and the way I pray.

“Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave” is at once a devastating disorientation and a liberating revelation. To take the perspective of the oppressed is to open yourself up to having all your beliefs that do not serve life undone, all your practices that are complicit with oppression interrogated. It is to be free to see the world as it truly is, without the paternalistic veneers that pander to our comfort.

There is only the fierce love that will not rest til all are free.

"I will not equivocate; I will not excuse"

I will use the severest language I can command…. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

Douglass asserts: there is nothing to be gained by trying to argue about abolition with unpersuadable people. A well-crafted argument will not somehow make the case against slavery more palatable to those whose conscience has been deadened.

The truth that is self-evident to Douglass, as it should be to everyone, is that slavery is wrong. It is a waste of breath to engage in debate on this point.

Rather, the righteousness of the cause demands the unvarnished truth. Its urgency requires denouncing loudly and clearly the heinous sin of slavery.

There is only one way to speak, and that is with moral clarity that reveals the hypocrisy of the nation.

Today, many well-intentioned people seek to prove the rights of, say, immigrants and refugees, by emphasizing how they are “hard-working, tax-paying, contributing members of our communities.”

Unfortunately, following Douglass’s logic, this assertion concedes ground to those who simply do not see immigrants as fully human (while also inadvertently dehumanizing people who do not fit in those categories), because it still presumes a hierarchy of human worth, in which people who work hard have more moral value than those who do not.

We waste energy trying to debate on the grounds of moral fitness, when what must be denounced is the whole damn system that demonizes and disposes of human beings. So much of the US project has been based upon disposability politics — distancing ourselves from these is an imperative paradigm shift.

As it could have been said in Douglass’s day, we cannot enslave our way to a free society, today it may be said: we will not abduct our way to affordable healthcare and quality education. And, separating families will not lead to community safety.

We must claim the moral high ground: No one should have to prove their humanity in order to be treated as human. A society that makes such demands is morally depraved and hellbent on self-destruction.

“your celebration is a sham”

There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour….for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

Douglass’s indictment rings down through the centuries. It is not only this nation’s wanton practice of violence that demands justice, but its wholesale denial of guilt — its stomach-turning claims of moral purity.

This whole project is held together by a hyper-fortified belief system.

“In the US, we’re told this is what keeps us safe: the bases, the bombs, the borders,”

wrote in this brilliant piece. “But militarism is not just policy, it’s theology. It shapes what we worship, what we fear, what we teach our children to sing.”The unholy trinity of bases, bombs, and borders is treated as sacrosanct. We are taught not to see these things as humanly constructed, but instead to treat them as eternal and god-ordained.

Douglass minces no words: The whole system, with its absurd pomp and circumstance, is ridiculous. A “sham.”

His boldness gives us permission to ask ourselves questions like:

Is “the rockets’ red glare” really something we want to sing out as US rockets are falling on Iran and Palestine, targeting schools, churches, mosques and hospitals?

Do we really want to feast on beer and BBQ while people are being picked off by snipers as they sprint, Squid-Game style, to get food in US and Israel-run “aid” centers?

Is there really any freedom to celebrate when the Miccosukee tribe is fighting a 5,000 person detention facility (read: concentration camp) planned for the Everglades dubbed Alligator Alcatraz?

The system is quite susceptible to such questions, because they reveal the nation’s moral superiority as the artifice it is.

“I do not despair of this country.”

There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. "The arm of the Lord is not shortened," and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.

In a startling turn, Douglass concludes on a note of hope, with a reflection on the way in which the world of his day was becoming increasingly interconnected. He believed globalization would eventually make the US a pariah amongst the nations of the world.

Douglass’s prediction of slavery’s doom would come to pass 11 years later, though some enslaved people wouldn’t get to taste freedom until 1865, when the Civil War ended and word of the Emancipation Proclamation was finally able to reach Galveston, Texas. Hence, Juneteenth celebrates how formerly enslaved people were finally all free. It’s significant that this is the day that Black leaders long campaigned to highlight as the celebration of Black freedom, because it is characterized by interconnectedness. By no one being one left behind.

At a time when authoritarian leaders in the US and around the world are trying to pull us back into fear, scapegoating, and isolationism, we resist their divide-and-conquer tactics by insisting on our connection to one another:

To our Black siblings. To our Indigenous kin. To our immigrant and refugee dear ones. To our trans and non-binary and queer and gay beloveds. To our loved ones with disabilities.

To those in Congo. And Sudan. And Palestine. And Iran. And Ukraine. And everywhere else where ordinary people are resisting the veil being violently pulled over the eyes of the world.

Perhaps the interconnectedness that gave Douglass such hope might just begin with asking questions like, “What, to the slave, is your Fourth of July?” and letting this dissonance trouble the waters of our souls.

I hope we set sail toward solidarity.